The Sociobiome Exposes Privilege Behind the Data

The microbes we study reflect not only biology but the privilege of who gets included, and who gets left out.

Two recent studies highlight how socioeconomic status (SES) leaves microbial fingerprints on the human gut, but they come to opposite conclusions about one of the field’s most basic metrics, diversity. Together they expose both the promise and the pitfalls of linking the microbiome to social inequality and point toward what the next generation of research must deliver.

Wisconsin: SES, Food Insecurity, and Antibiotic Resistance

Zúñiga-Chaves and colleagues (npj Biofilms and Microbiomes, 2023) studied over 700 adults from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin . Using the Economic Hardship Index, they found that people living in high-hardship neighborhoods had lower microbial diversity, and that food insecurity partly explained the effect. They went further than diversity and composition and found individuals in these neighborhoods were also more likely to carry multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs). This connection between community hardship, microbiome disruption, and antibiotic resistance provides one of the first clinical footholds for the field.

New York: SES, Diversity, and the Multi-Ethnic Sociobiome

Kwak and colleagues (npj Biofilms and Microbiomes, 2024) analyzed 825 adults from the racially and ethnically diverse FAMiLI study. They found that lower education was linked to higher microbial diversity, not lower, and that neighborhood deprivation explained small but significant differences in community composition. Specific taxa emerged as SES-sensitive: Prevotella copri and Catenibacterium were enriched in lower SES groups, while Dysosmobacter welbionis was enriched in higher SES groups. They showed that race, ethnicity, and nativity were deeply intertwined with SES, making it impossible to untangle microbial signatures of class from those of culture and migration.

Reconciling Contradictions

Why does one study say low SES means lower diversity while the other says higher? There are at least three explanations.

Geography and demography: Wisconsin’s cohort was mostly White and Midwestern; New York’s was multi-ethnic and immigrant-rich.

SES measurement: Wisconsin used a single neighborhood hardship index; New York combined both individual- and neighborhood-level indicators.

Microbial metrics: Both studies used 16S rRNA amplicons but with different rarefaction depths (8,396 vs 1,000 reads). Neither approach gives species-level certainty, yet both papers discuss Prevotella and Dysosmobacter as if they were resolved to the genome.

The contradiction may not be a bug, it may be the true signal. SES influences microbiomes not in a universal direction but through local diets, environments, and social structures.

What We Learn About the Sociobiome

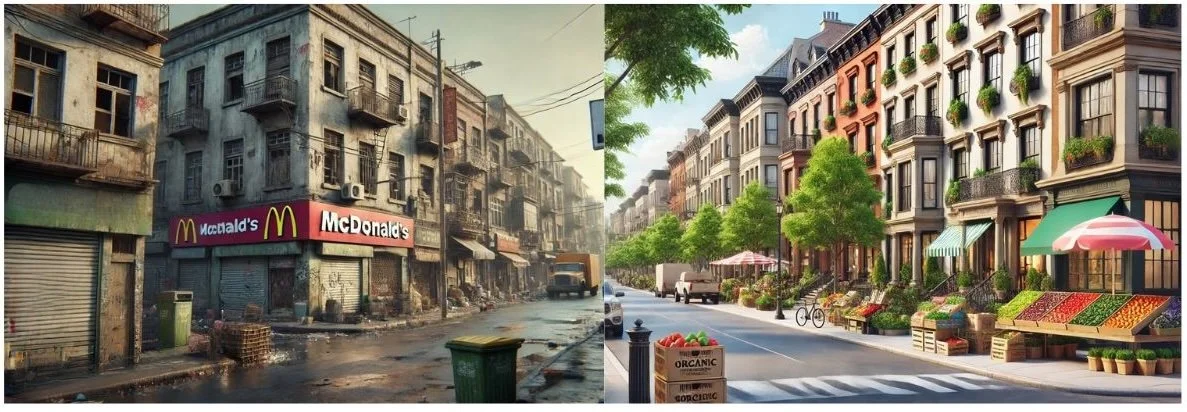

Both papers add weight to the emerging concept of the sociobiome, which is the recognition that microbial ecologies are not only biological systems shaped by diet and host physiology, but also by social systems reflecting the inequities of the neighborhoods where people live. The gut is not sealed off from the social world. It records the quality of food available in local markets, the crowding of homes, the stress of economic hardship, the cultural practices that come with migration, and the structural barriers to healthcare.

The Wisconsin study highlights the material consequences of deprivation whereby food insecurity mediated the loss of microbial diversity, and those living in harder-hit neighborhoods were more likely to carry multidrug-resistant organisms. This places the microbiome squarely in the pathway linking poverty to higher infectious disease risk.

The New York study shows a different but complementary picture. Here, nativity, race, and acculturation intersect with SES to shape the microbiome. Low-income neighborhoods were associated with specific microbial profiles, but those signals could not be separated from the cultural and dietary patterns that come with being foreign-born or part of a minoritized community. Rather than contradiction, this underscores a truth. SES does not operate in a vacuum, it collides with ethnicity, migration, and history to produce unique microbial signatures.

Taken together, the message is clear. The microbiome becomes a biological register of inequality, a living readout of social conditions that accumulate over a lifetime. It is not enough to study microbes as if they were purely products of calories and fiber. They are also products of policy, geography, discrimination, and access. To talk about “the human microbiome” without grappling with the sociobiome is to ignore the way social inequity literally colonizes the gut.

And here is the uncomfortable reality, most microbiome research comes from the United States and Europe, where convenience sampling of largely White, middle-class cohorts is treated as the default. This creates the illusion of a “universal human microbiome,” when in fact the data are geographically narrow and socially biased. By ignoring the sociobiome, we flatten cultural variation, erase structural inequities, and overstate the generalizability of our findings.

What Needs to Happen Next

Both papers suffer from predictable weaknesses:

16S amplicons with species-level claims: We need shotgun metagenomics and metabolomics, not inference stacked on inference.

Cross-sectional design: Association is not causation. Longitudinal and interventional work is essential.

Tiny effect sizes: SES explained about 1% of the variance in microbiome composition. Statistically real, but biologically modest.

The future of sociobiome research will hinge on integrating causal frameworks, richer -omics, and mechanistic validation. Imagine pairing geocoded hardship indices with longitudinal stool samples, metabolomics, and clinical outcomes. Imagine testing whether improving food security in a community changes not just diets, but gut microbial resilience and resistance to pathogens.

The Bigger Problem We Cannot Ignore

These studies also highlight a deeper issue: most microbiome research comes from high-income countries, primarily the US and Europe. We keep trying to extract universal truths about “the human microbiome” from cohorts that are geographically narrow and socially stratified. SES is treated as an afterthought or nuisance variable rather than as a central force shaping exposure, diet, and even pathogen risk. That is a mistake.

If we continue to ignore context, we will keep producing contradictory findings about something as basic as diversity. The Wisconsin and New York studies show that microbes do not just reflect calories and fiber, they mirror the politics of food insecurity, the legacy of immigration, and the design of the neighborhoods where people live.

The lesson is clear. If the microbiome is to play a role in health equity, then equity must play a role in microbiome research. If we are serious about understanding the human microbiome, we must design studies that treat social determinants as first-order variables, not statistical noise to be controlled away. We need global, diverse, context-rich cohorts, not just more sequencing of privileged populations. Otherwise, microbiome science will keep producing contradictory findings about something as basic as diversity, because it is still blind to the social world in which microbes actually live.

The sociobiome forces us to see that the ‘normal microbiome’ is too often defined by the privileged. True progress means studying the guts of those whose lives are shaped by hardship, not just convenience.